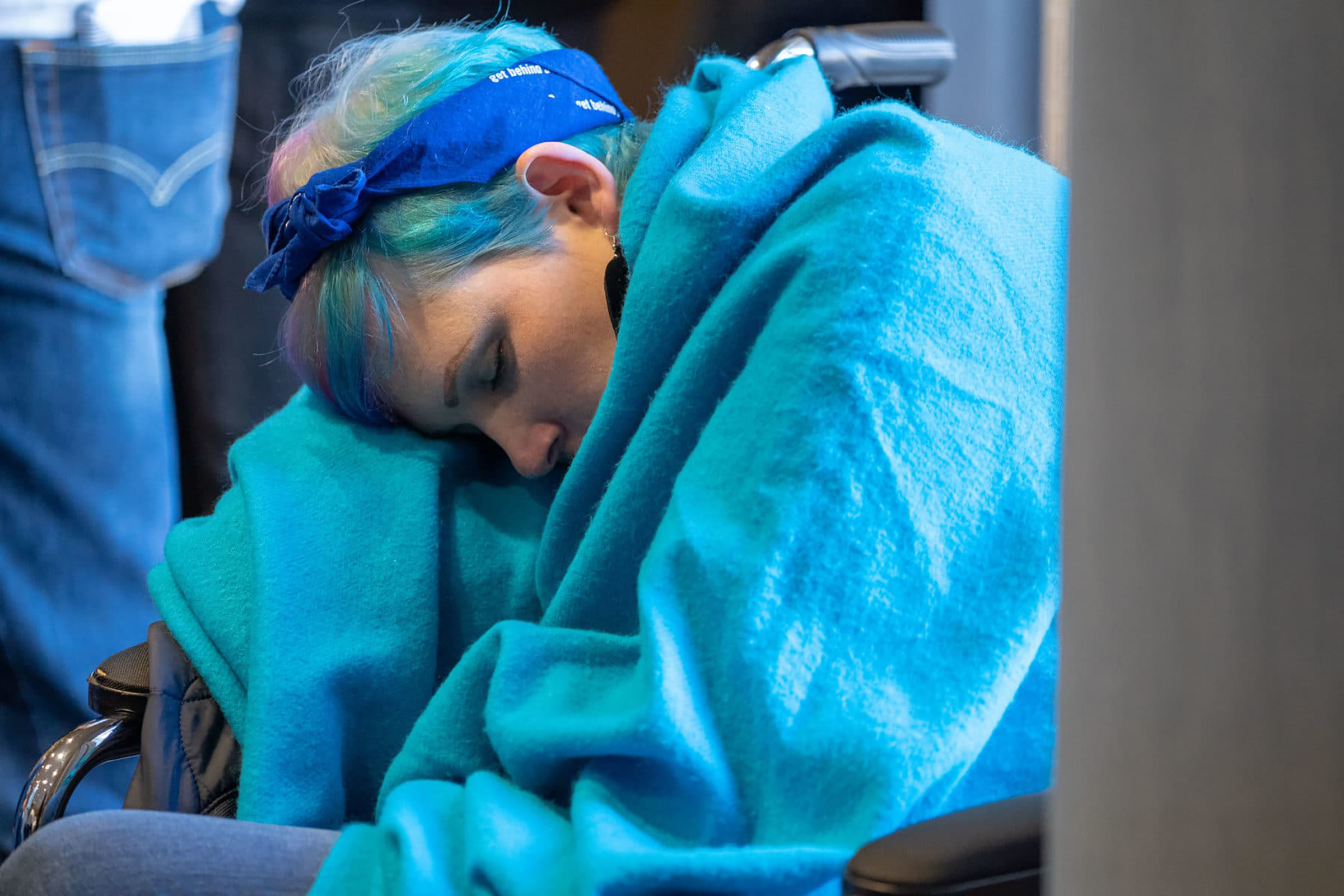

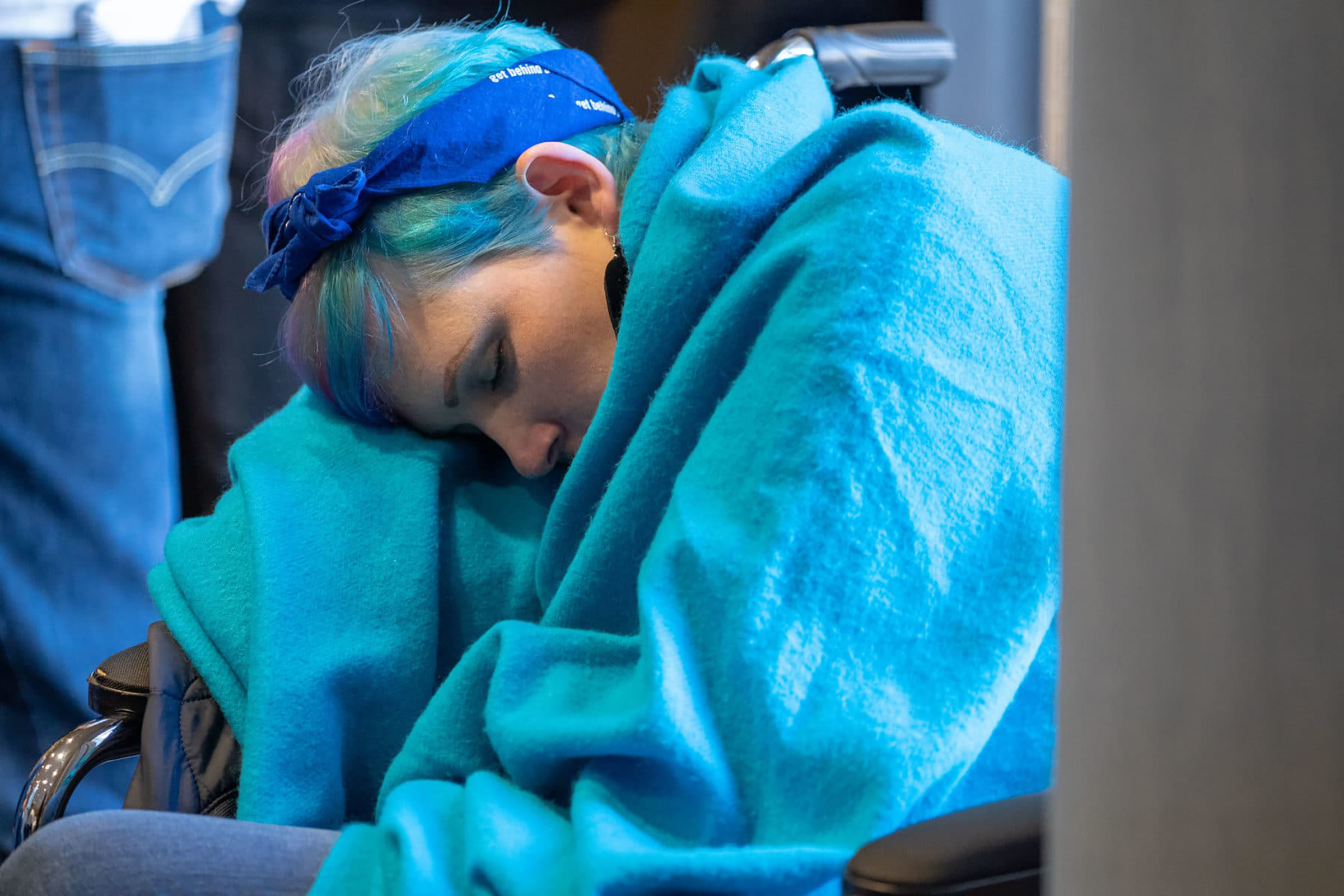

Cancer-Related Fatigue

Feeling worn out and exhausted all the time? You may be experiencing cancer-related fatigue. Tune in to this webinar to learn what cancer-related fatigue is, how to spot it, and how to manage it.

Feeling worn out and exhausted all the time? You may be experiencing cancer-related fatigue. Tune in to this webinar to learn what cancer-related fatigue is, how to spot it, and how to manage it.